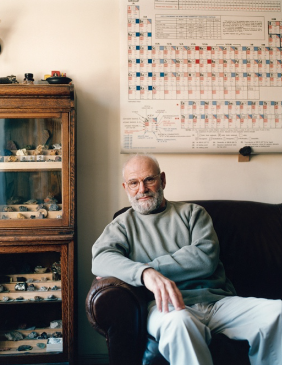

Oliver Sacks

10/02/25, 14:25

Last updated:

21/01/24, 11:54

Published:

A life of neurology and literature

If I had to credit one person for introducing me to the subject that would become my career choice, it would be Oliver Sacks. Trying to develop my interests and finding myself in a world of science textbooks that sounded too complicated – and often simply pedantic – made me desperate to find something that could somehow combine my love for science and my fondness for literature. Luckily, I managed to stumble upon “the poet laureate of literature”, a physician who presented real characters with true medical cases without putting a teenage girl to sleep.

Oliver Wolf Sacks was born in London in 1933. He grew up in a family of doctors; his mother was one of the first female surgeons in England and his father, a general practitioner. His interest in science started at a young age, experimenting with his home chemistry set. Following in his parents’ footsteps, he went on to study medicine at The University of Oxford before moving to the US for residency opportunities in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Although he enjoyed the sweeter life on the West Coast, by 1965 he decided to take a more permanent residence in New York, where he continued to work as a neurologist as well as eventually teaching at Columbia and NYU. It was in the city of dreams where he started his literary journey.

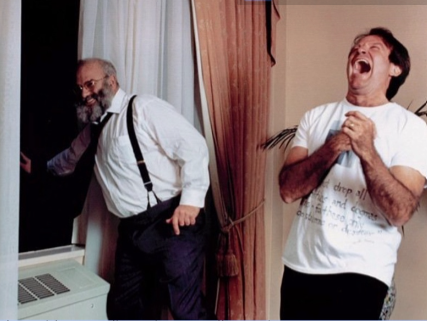

One of his main creative inspirations was born from his time as a consultant neurologist at

Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx. There, he found a group of patients who had been in a catatonic state due to encephalitis lethargica. They appeared frozen, trapped in their own bodies, unable to come out. Sacks decided to start a series of trials with L-Dopa, a dopamine precursor drug which was then still in the experimental stage as a treatment for Parkinson’s. Almost miraculously, some of the patients started “waking up” and regaining some movement ability. Although the treatment was not without flaws, the satisfaction of helping his patients and the close relationships he came to develop with them after caring for them for months really touched Sacks. In 1973, he published his narration of the events in Awakenings, a bestseller that was later adapted into a film of the same name starring

Robin Williams and Robert de Niro.

Oliver Sacks went on to write about music therapy, a rare community of colourblind

individuals and his own experience both as a doctor and as a patient, among others. His

most notable works are probably “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” and “An

Anthropologist on Mars”. Both describe in detail fascinating case studies, ranging from more known conditions such as Parkinson’s, epilepsy and schizophrenia, to other relatively more obscure diagnoses at the time including Tourette’s, musical hallucinations and autism. The condition that took my attention the most when reading “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” was that which gives the book its title. The man who could not tell apart his hat from his spouse was diagnosed with agnosia: the inability to recognise objects, people or animals as a result of neurological damage along pathways connecting primary sensory areas. Agnosia can affect visual, auditory, tactile or facial recognition (prosopagnosia), or a combination of these.

Crucially, Sacks’s works showcase not only a recount of symptoms and abnormalities, but a

tale of people who retained their humanity and individuality beyond their medical

diagnoses. As he told People magazine in 1986, he loved to discover potential in people who weren’t thought to have any. Instead of merely fitting patients into disease, he liked. To observe how they experienced the world in their unique ways, recognising difference as a path to resilience rather than just a handicap.

Written by Julia Ruiz Rua

Project Gallery